When Carolyn Lumsden got her first-ever journalism article pitch accepted, an interview with the writer Christo, there was one catch. “The problem was, I hadn’t done any such interview,” Lumsden says. “I’d never met Christo.”

A 26-year veteran of Connecticut’s largest newspaper opinion section, Lumsden has won not one but two Sigma Delta Chi Awards in Editorial Writing from the Society of Professional Journalists.

In 2017, her four-part editorial series “Crumbling Foundations” spotlighted tens of thousands of Connecticut homes made with pyrrhotite, a little-known material that causes foundations to easily deteriorate. In 1995, her three-part editorial series “Justice in the Dark” helped convince the state to reform the confidentiality laws for trials involving juveniles.

But before that job, before her job as a reporter for the Associated Press, Lumsden’s first-ever journalism interview — her first ever — was with Christo. The experimental artist, who died in May 2020, spent decades attempting among the most audacious and largest-scale art projects in memory, including 1995’s wrapping of the entire German Reichstag building in fabric and 2005’s installation of thousands of bright orange gates in New York City’s Central Park.

2005’s “The Gates” exhibit in New York City. Credit: Wikimedia user Delaywaves.

Here’s what she remembers about landing that first interview, and how it set her on the decades-long journalism path she eventually pursued to great success.

The artist Christo was my first interview ever.

It was the spring of 1978. I had a lowly job in New York City. Tired of that and desperate to get my name in print, I called Soho Weekly News, a chic paper in lower Manhattan. [The publication existed from 1973 to 1982.] An editor there said yes, he would look at my interview with Christo.

The problem was, I hadn’t done any such interview. I’d never met Christo.

I then called Christo. It was easy to find phone numbers in those days. I told him that Soho Weekly News wanted a story on him. He said OK.

A few days later, a thin, shaggy-haired Christo opened the door to his loft. He looked and sounded like an intense professor. His loft was hung with photographs of his mammoth projects: Wrapped Coast in Australia, Valley Curtain in Colorado, and Running Fence in California.

Of course, there was a large mysterious package in the living room. Christo called it Wrapped Canvases.

I offered him the expensive bottle of wine I could barely afford. He ignored it. He set to work, dictating ideas and opinions.

“We live in the most political, social, economic century of human history,” he lectured. “I think that any art that is less than political, less than social, less than economic, is certainly less than contemporary art.” And so it went for an hour.

He talked about clashes over his projects, including one dustup involving wrapping walkways in Kansas City. “We have so many problems in trying to get the permits! … Some people around the community think that doing the project will create a fantastic traffic jam … And that the park will become the place of marijuana smokers and drunkards. And who will collect the garbage?”

The projects usually ended up making people happy and giving them great memories.

After an hour, [Christo’s wife and artistic collaborator] Jeanne-Claude came home. She also had shaggy hair, but she looked more like a fashionable art curator, and she praised my gift of wine. It was a moment of triumph.

The story ran in April 1978. When Christo died earlier this year, I went looking for the article online and found that the Whitney Museum of American Art had excerpted it for the exhibition catalog called “Surveying the Seventies.”

I’m grateful to Christo for taking me seriously and giving me such a wonderful first-ever interview.

Here’s an excerpt from the actual article:

I think we live in the most political, social, economic century of human history. It is unprecedented… I think that any art that is less than political, less than social, less than economic, is certainly less than contemporary art. We cannot stop that concern, we cannot stop that dimension of art…

Of course, all the activity created the momentum of the project [Running Fence]. Without that, the project would not have had its impact. The project created forces for and against. All my projects have that same character because they are built outside of the art system. The art system is anything from the National Endowment for the Arts to the private galleries to the museum collector who dictates what is avant-garde and contemporary art. Because the project was put outside of that system, it was in subversive relation to the structure of perception of what is art, what is permitted. That is the source of energy of the project.

From Carolyn Lumsden, “Christo: ‘I Am a Political Artist,'” Soho Weekly News, April 6, 1978, p. 20.

Follow her on Twitter @CarolynLumsden. And do yourself a favor and read the series of editorials and op-eds she spearheaded in the wake of the 2012 Sandy Hook mass shooting.

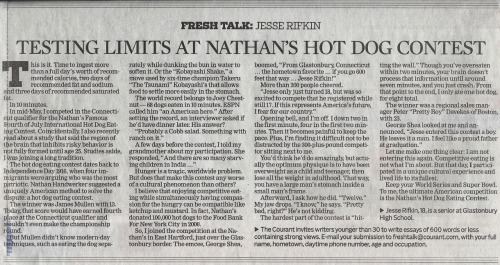

On a personal note, Carolyn repaid the favor that the Soho Weekly News first paid her, by greenlighting my own first-ever “real” journalism experience outside of my high school newspaper, with my 2010 op-ed about competing in a hot dog eating contest:

Nicely done. That shows chutzpah on her part reaching out to Soho Weekly.

LikeLike